Ballroom competitions, along with the breakdance battles of the ’80s, and rap crews spitting sixteen bars for glory and validation, have often been compared to the world’s most safe and constructive gangs, and the idea that a lot of this is done through the body, in the context of this Resmaa Menakem’s book My Grandmother’s Hands, substantiates them as “potential movements [and] forces for tremendous good in the world.”

One day, several years ago, Menakem laid out the thesis of his book on 10% Hap- pier, a podcast I listen to that’s hosted by ABC News anchor Dan Harris about the positive effects of meditation and mindfulness practices on our everyday lives. Along with therapy and actual meditation, through interviews with contemplative masters, 10% helped me personally process the familial and systemic trauma residing within my own body. That day, the same day that two other friends recommended My Grandmother’s Hands, Menakem came on the show and explained how his grandmother was a sharecropper and how her hands were therefore never supple, how such hardships are passed on hereditarily through epigens. To that point, he said the reason he chooses to use the term “white-body supremacy,” as opposed to “white supremacy,” is because the effects show up in our DNA and are most manifested in our bodies.

So, I conceded and bought the book later that day. As everyone suggested, it ended up for me being a crucial way to understand surviving, acknowledging, and metabolizing racial trauma in this very moment in time in America—through the body. It lays out a path of not avoiding but feeling and processing the damages of racial inequality, allowing it space so that its darkness doesn’t envelop us. How the body isn’t just a tool for trauma recovery but rather the first and most essential place, even more than the mind. Whether you’re interested or not, I suggest you pick up a copy of My Grandmother’s Hands, and actually, if you’re not interested, you probably need to read it the most. Personally, it helped recalibrate my framework for this body section of the book.

Yes, “body (yadi-yadi)” is a category walked by mostly fem queens and others at a ball, those most bodacious (in all aspects of the word) dominating the category and walking the runway like they’re proud of it. Judges might cop a feel. Tight or revealing clothing is welcome. I’ve seen the girls and butch queens show up body oiled. As with realness, the body category might also mean a certain level of commitment and access to augmentation, as bangin’ bosoms, curves, and hips are all classic accoutrements to the category and tend to spark tens across the board. This category is liberating because, unlike high-fashion categories like town and country or Madison Avenue, it actually reinforces and celebrates non-white standards of beauty, albeit often at the hazard of folks who go to great lengths to achieve these features. But again, this is the ongoing balancing act of real vs. realness, the line of which is thankfully drawn subjectively.

And that’s all interesting, but this idea of how we can individually and collectively reenact or instead metabolize and recover from trauma in our bodies is most intriguing. How being a trans woman successfully walking body after your hormonal and/or physical transition, finally being heralded for your femininity by your peers after being physically threatened, endangered, and brutalized by the outside world for not blending in, might just be a type of bodily recovery from a lifetime of such trauma. My friend the journalist Channing Gerard Joseph writes about William Dorsey Swann, or “Queen,” a former enslaved person from the nineteenth century—and likely the first drag queen, who threw then illegal drag parties (basically balls), physical gatherings or movements of bodies settling together in defiance, often considered by police and newspapers at the time as riffraffs or a mob of undesirables.4 Perhaps predating a more apt nomenclature, in today’s context, would Swann and his cohort actually be seen as trans women? If so, was it healing, an act of relief, a form of collective recovery and personal reclamation for her to put on those parties, where she and others could wear dresses and be who they truly were? Was this Jim Crow–era sanctuary an even riskier preamble to walking realness at a ball today? If nothing else, theirs was one of the first LGBTQ movements devoted to recovering from the persecutions of generational trauma, namely enslavement and gender discrimination.

We often talk about the lineage of voguing. How a spin and dip on the four beat, the hands of everyone in the room hitting the floor simultaneously, everyone shouting “Oh!,” is the sight and sound of your inheritance, reverberating off your bones and echoing off the ceiling so loud the ancestors must have felt it. If we can hear them, then in theory they must hear us. Or how vogue is what ancient Egyptians planted in us, hieroglyphic stories of peace, war, victory, and failure that blossom up from us in flourishes of revolutionary dance. How voguing then becomes a living archive within us and how, based on this foundation, voguing is also a way to tell our own modern stories, the passing of a baton in an epic, historical relay race charting the Black and brown experience. How we are also voguing narratives of our enslaved ancestors, and because their stories, their names, their families and culture were ripped from them in the transatlantic trade, voguing is their unerasable inscription, because only print can be redacted, not spiritual movement. In this context, vogue is a defiant, bodily act of collective recovery from ills that are the spoils of the capitalist war. We know that, at their best, Black and brown queer bodies voguing at a ball is an act of capitalist abolishment—but to what magnitude? Does it heal the past? Recourse the future? Create an alternate universe? Transcend time? The answer is yes.

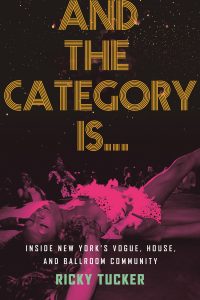

Reprinted with permission from And the Category Is…: Inside New York’s Vogue, House, and Ballroom Community by Ricky Tucker (Beacon Press, 2022). Available from Amazon and Bookshop.