People come to nonmonogamy from many different starting points. For some, no matter how hard they tried, the monogamous paradigm never felt quite right, and their relational world only made sense when they discovered consensual nonmonogamy (CNM). Others may have initially experienced monogamy like a comfortable pair of shoes that eventually wore thin and needed to be changed out for something that fit better. Some are drawn to CNM because they have struggled with the exclusivity of being with only one person, or they have felt philosophically misaligned with the tenets of monogamy and find more resonance with the principles and practices of CNM. Some find their way into CNM through kink or queer avenues—via their experience with a different paradigm altogether. Others, despite their faithfulness to their partner, have inwardly longed for more relational and sexual diversity and desire the opportunity to have new experiences. For some, leaving behind monogamy was a very conscious and deliberate decision, which clearly necessitated the search for a new paradigm to guide their journey. For still others, the idea of CNM would never have even crossed their minds unless it was from someone else, such as a close friend or curious partner, introducing it to them.

Just as the paths that lead people to nonmonogamy can be very different, so, too, are the processes of integrating a nonmonogamous paradigm. For example, some people experience nonmonogamy as if it were the lost blueprint of their romantic essence. Something in their soul just seems to recognize its wisdom, and they embody it with relatively little resistance or struggle. For others, however, the integration process can be much less elegant or easy. Some are drawn to the philosophy and principles of nonmonogamy but struggle with managing the challenges that arise in their relationships. Even though they resonate intellectually and emotionally with the tenets of nonmonogamy, their nervous system—conditioned by years of monogamous expectations—can struggle to accept the changes that come along with practicing it. In such cases, people can experience a kind of CNM paradigm jet lag where their nervous system needs time to rewire itself and catch up to the new reality. It’s simply not enough to be on board with the ideas of nonmonogamy: we must also integrate the new worldview into our very ways of relating. This, for many, is easier said than done.

When looking back at some of the major paradigm shifts that I, myself, have made over the years, I am reminded that each big life change was either helped or hindered by a series of different factors and circumstances. When comparing some of those previous experiences, I am able to better understand the unique constellation of conditions that ultimately paved the way for my transition into new paradigms. For instance, when I first read about Buddhism, when I was around 18 years old, it was very easy for me to cast aside the Catholic and Jewish beliefs that I grew up immersed in. I had an immediate resonance with the philosophical underpinnings of Buddhism that just felt intuitively in alignment with how I perceived the world to be. I was already aware of the fact that the Judeo- Christian worldview of my larger social environment was incongruent with many of my core political, moral and spiritual values, and thus, there simply wasn’t much psychic residue from the dominant religious narrative for me to excavate or rid myself of. To make matters easier, I experienced zero resistance from anyone important in my life about changing my spiritual and philosophical beliefs. Numerous resources were also readily available on bookstore shelves on Eastern philosophy, meditation and mindfulness, which greatly facilitated my spiritual paradigm shift. I had the advantage of having plenty of retreats, spiritual teachers and local meditation groups to choose from, and my family and friends were mostly curious, even eager, to hear about the changes I was making. So, even though I was technically entering into a minority paradigm–in terms of the socio- spiritual context in which I lived–I experienced absolutely no marginalization.

Changing my diet in my mid-twenties after developing serious autoimmune issues of the gut was another story. I was diagnosed with a significant allergy to not only gluten but all grains as well. Even though I was raised eating gluten-dense foods for breakfast, lunch and dinner and was vegetarian for years, I was forced to make a complete one-eighty with my eating habits, from vegetarian to paleo, practically overnight. To this day, eating out in restaurants remains extremely challenging because I am constantly faced with the possibility I will be served foods that could cause serious immune reactions. This has also meant that seemingly normal activities such as buying food at a regular grocery store, eating out with colleagues at conferences, or attending social events are complicated—or simply not an option anymore. This has led me to seek a radically different paradigm of food, nutrition and health from the one I was raised in and which is still prevalent in the world at large.

My whole relationship to food has drastically changed: where previously I could take advantage of the conveniences of dining out or grabbing something on the go, I now have to cook almost all of my own meals every single day, consuming a significant amount of time that, quite frankly, I would prefer to spend doing other things. Even the typical dating options to meet over drinks or dinner are usually off the table for me due to my food restrictions. But as much as it’s a pain in the ass to function within the parameters of this laborious alternative food paradigm, which has had an extremely isolating impact on my social life, I’m actually fully on board with it. Despite the challenges implicit in the new lifestyle, I’m healthier because of the changes I’ve made, and I have actually healed my gut as well as the associated mental health issues I had experienced as a result of my autoimmune condition.

When comparing my experiences of changing my spiritual and culinary paradigms—despite the fact that only one of these paradigm shifts meant facing significant and difficult consequences externally—internally my experience of making both of these changes felt relatively similar. The thing they both share is alignment, a deep clarity that these paradigm shifts were necessary and undeniable regardless of the possible external implications that accompanied their implementation. Inwardly, I felt no vacillation, no resistance. Thus it didn’t matter to me if the world agreed with my decision or not. It was precisely this intrinsic congruence that made the changes feel doable, even in moments of difficulty or inconvenience.

For some people, the transition to CNM is like mine with Buddhism: it resonates with who they feel themselves to be; their hearts and minds experience little to no resistance to the shift; and they may even experience little social impact from technically being in a minority. People who experience their shift from monogamy to nonmonogamy in this way may then also find it difficult to understand why the transition can be so challenging for their partners. On the flip side, people who don’t experience their shift to CNM with this level of ease and grace may judge themselves for the difficulties they face, taking on the story that they should be able to make the change without difficulty, struggle or resistance. For other people, their paradigm shift to nonmonogamy looks more like my experience with my diet, where the choice to make the shift wasn’t something they would have necessarily chosen on their own but, because of life circumstances, was necessary to take on, and they remained committed to seeing it through. Over time, they recognized how nonmonogamy was actually more in alignment with their personal values, and they realized they wouldn’t go back to monogamy even if they could, despite the ostensible convenience and comfort it seems to offer.

But what about the paradigms that feel harder to get on board with internally? For example, practically every time I start shaving my legs in the shower, I am painfully reminded of how patriarchy has influenced my perception of my own body, making me judge my own legs as prettier when shaved than in their natural, hairful state. Why, after so much conscious effort to deconstruct the expectations of capitalist beauty culture, and after so many books and courses on how to love my body no matter what it looks like, do I still struggle with my body image? From over- exercising to undereating, I have, at times, literally done myself harm in the name of being thin. Even though I conceptually know that beauty is subjective, socially constructed and ever- changing throughout history, I have nevertheless internalized the false belief that, as a white, cisgender woman, I am supposed to look a certain way. And if I don’t, my attractiveness, value, lovability, worthiness and womanliness are all called into question. When the inner voice of the body critic kicks up, it’s like a virus taking over my mind, getting me to think and behave in ways that are actually harmful to myself.

Over the past two decades, I have come a long way, but the shift into full body positivity is still very much a work in progress. Compared with other paradigmatic shifts I’ve made, this one feels glacial, and beyond my capacity to just hurry along. Thankfully, I am no longer imprisoned the same ways I used to be, and I can see the old paradigm for what it is and relate to it differently. However, it would be a lie to say I no longer feel or experience the very real and concrete impacts of those narratives on my sense of self. Despite my lucid recognition of its fallacy and all my best efforts to undo my attachment to the story that I need to look a certain way in order to be worthy, at times, I still fall under its spell. The spell of a paradigm I am actively resisting.

Similarly, for many of us the integration of consensual nonmonogamy into our relational lives is not a quick, easy or pain-free process. Whether pursuing CNM as an orientation, as an experiment, or for philosophical reasons, we can still experience significant resistance and difficulty as we detox from the deeply ingrained ideas of monogamy that continue to linger in our consciousnesses. Regardless of whether you are new to open relating or have been polyamorous for years, sometimes it can feel as though you’re trying to let go of a paradigm that doesn’t want to let go of you! When you add the moral judgments of a puritanical, monogamous culture or the negative opinions and potential rejection of friends and loved ones, it can become extremely challenging to fully embrace and embody consensual nonmonogamy in the ways you really want to.

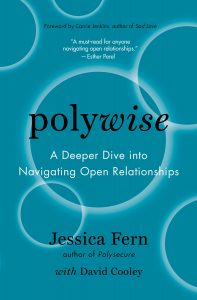

Originally published in Polywise: A Deeper Dive into Navigating Open Relationships, © 2023 by Jessica Fern with David Cooley. Republished with permission from Thornapple Press.

Polywise is available from Amazon and Bookshop.