The older I get, the more is expected of me. Whether it’s in my career or my personal life – I am expected to succeed in the way only a woman can – and that is usually with a family. But family aside, I am also expected to have a set of values and morals that align with the older and somewhat defunct generation of women who have struggled. One thing I should definitely not be is outspoken. If any of my family is reading this book and consider it to be a horrific tale of how an Indian woman lost her way … this is directed at you.

I’ve been told far too many times to keep quiet.

I’ve been told what I’m doing is wrong.

I’ve been asked why I don’t have any shame.

I’ve been laughed at.

I’ve been considered uneducated and angry, instead of insightful and empowered.

All of these things echo in the lives of many people, especially for women of colour. It’s unbecoming of me to talk about sex. It’s unnatural for me to want to be with a woman or non-binary person. It’s annoying when I talk politics. The things I say aren’t true, because I don’t actually know what’s happening in the world.

Whether I will ever be taken seriously or not by a certain generation or family members has got a lot to do with my decisions as I age. If I don’t spend this time cultivating a modest lifestyle (although modesty means having lots of money) that people can discuss with a sense of pride, then when I speak, no one cares to pay attention.

Although, as a woman, if I speak with the modesty they hope I have, they still wouldn’t listen. There’s no winning here. But this isn’t a game, this is about people’s livelihoods.

The older I get, the more I’m taken seriously, sure. But it comes at a cost. ‘Okay Sharan, that’s interesting, but are you making enough money? Are you thinking of buying a house yet? When will you get married? Are you too old for children now? Are you concentrating on these things and ignoring your personal life’.

And so I think … ’am I?’

Are the decisions I’m making to try and enact change, to connect to communities and to bring people together – is that creating a larger distance between me and my personal goals? It’s something I think about a lot, because I find it especially difficult to separate life and work.

When examining this over the years, I came to find that there’s no real difference between the two. And why should there be?

What is this ‘personal life’ people speak about? Is it taking time to have a long bath? Or is it about buying lots of plants for your house? Has it got something to do with the partner you choose? Maybe the number of times you see your family?

One thing I can’t escape as an Indian woman is the concept of ‘shame’. I am, in all manners, a shameless woman – a ‘Besharam’. Hence it means someone who is not shy of anything; someone who does not think or care about the way they are perceived – more precisely, someone who is shameless. Because I refuse to live my life by a certain set of rules and expectations, I am not a good person. This means that I am not talked about in a high esteem (unless I get on TV … although even then I’ve been muted, in case I was saying anything unbecoming). Instead, I’m discussed in hushed tones, where rumours start, and heads shake in disbelief.

When people gather to gossip, they say: ‘Did you hear Meenu’s daughter is married now to a business owner!’ Maybe it’s followed up with: ‘Did you hear about Dhaliwal’s daughter? Thirty-Seven and still not married? And she’s gay? Disgusting’.

I have a very open social media rule – I don’t hide my life from people because I don’t believe that women should be silenced or restricted. Unless they decide to keep something to themselves, there shouldn’t be any shame put on their existence. So, I talk about my mental health, my work, my sexuality, my politics and – the thing that has given me the most intense headaches – my sexual activities. In fact, I’m an avid selfie taker and in the process, I find my sexual nature shines through. Possibly just to throw in the faces of those who don’t want me to, I post images of myself in lingerie, half-dressed or suggestive and I find liberation in it. It’s a form of rebellion, I suppose, something I will never grow out of – but it is what has helped me figure out myself and my body. It was through social media that I found the strength to come out. It was there I built my magazine, made friendships, collaborations, found work and so on. None of these things wouldn’t have happened if I wasn’t unashamedly myself.

When it comes to being sexually liberated, though – that’s where I’ve found the most pushback from my community and family. I find it funny when I think about India’s sexually liberated history and fluidity, to how I’m treated for posting a selfie with a bit of underboob, to show off a tattoo.

Historically, we’ve had the Kama Sutra that has shown India as a sexually liberated country. As discussed in a previous chapter, India’s history with sex is really complicated. Now I’ve talked about the Kama Sutra in a particular way, but in reality, the part of the text that looks at sexual techniques is a small section of it. A lot is about romance. It’s about the importance of romance, desire and love. It’s not pages and pages of sex positions other than missionary. Although those are fun to read through and at times practise (do it safely, some of these positions require some real skill and I don’t have balance when I stand perfectly still), it’s important to remember that the text has been viewed and translated through the eyes of a white man: Richard Francis Burton. So, the reality of the text which was compiled (maybe) sometime in 2nd and 4th century AD (so much is unknown about this including the real author), is about living well, economics, pleasure and love. What it essentially does is normalises sex within the narrative of life. Realising it’s more than a ‘sex book’, is a lot more empowering. By allowing sex to exist alongside the philosophy of life, it refutes any shame that comes with sexual acts.

And despite this history, people will talk about sexual liberation as a moment of shame. It makes you filthy – dirty, you need to be cleaned and taught the right way. I know that unlearning my liberation will mould me into their ideals – to conform. I don’t believe I’m here to conform to anything, not only because I’m a stubborn bitch, but because I am curious. I think the reason that many people find sex to be shameful is because of the pleasure that comes with it. It’s not like the pleasure of eating food, where you go ‘yum, this is lovely, give me more’. An orgasm creates a full body spasm that some consider a temporary enlightenment: experiencing true nirvana. And women, well … women aren’t meant to feel pleasure. They exist truly for one reason and that’s to procreate. The connection between procreation and sex is so ironic, I don’t even know where to start. But yet again, it’s not about the woman’s pleasure – you must please the man enough for him to ejaculate children into you.

But it is also quite frankly, incredibly patriarchal. The Kama Sutra describes how to pleasure a man and although the clitoris is barely mentioned, it’s rarely done in a way that is for a woman’s own pleasure. It also talks a lot about caste systems, it considers certain women unworthy, it says that only ‘maids’ should perform oral acts, it calls some women ‘smelly’ and ‘dirty’. Whereas men are rarely considered in this way. So even through a form of liberation, we are still unworthy.

I have been very open about the fact that I am and always will be a very sexual person. I really enjoy sex and I’m curious about it. I want to understand and learn

the depths of it. I want to consider it alongside love: the difference in how that feels. I want to think about organs and ailments, and how they react to certain sexual acts.

I want to think about fertility in terms of sex. But mostly, I want the autonomy to feel pleasure when I want, without someone telling me I’m not allowed. Because firstly, who are these people? Secondly, how did they come to existence without sex? Thirdly, I can’t live my life according to someone else’s belief structure. I refer back to the ‘I’m a stubborn bitch’ comment made earlier.

I’m stubborn and I’m curious. And I’m infuriated that curiosity has become shameful.

The thing is, you often hear people talk about a child’s curiosity with such delight, but when you hit a certain age, the delight is replaced with disgust. As soon as your curiosity questions their norms, you are no longer curious, but disruptive. A child can ask a million questions about banal things, followed by ‘oohs and aahs’ from the surrounding aunties and uncles, but when it questions something that would be considered ‘wrong’ – such as sexual preference or gender identity, instead of allowing a freedom to explore, they are ‘corrected’. This keeps happening until they believe what they are told, because why wouldn’t you trust adults?

But when you’re older, you can’t be moulded by them anymore, so they no longer feel delight in you. They definitely don’t like you. This is true for many women, and specifically for the sake of this conversation, Indian women.

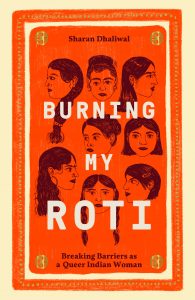

Excerpted with permission from Burning My Roti by Sharan Dhaliwal, published by Hardie Grant, April 2022, RRP $22.99 Hardcover.

Burning My Roti: Breaking Barriers as a Queer Indian Woman is available from Amazon and Bookshop.