Black Indie Romance is the baddest chick in the room.

Dressed to the nines—maybe a little inappropriately, but really, who’s to say?

Those whose names “belong” on the list sneer at her, wondering how she could have snuck in. The true, hardcore fans recognize her. They smile when they see her there, feeling proud of the fact that they supported her before the “mainstream” knew her name or saw her face.

While everybody else is whispering, picking apart her flaws, snickering behind their hands about her unworthiness, all the ways she’s not like them, not as good as them… She stands strong.

Confident.

Knowing that if nothing else… The room is talking about her, even if later they swear they have no idea who she is.

If that analogy is a stretch to you, maybe you haven’t been paying attention to the romance landscape. Through the years, romance has struggled to find its place in the literary community, often overlooked or looked down upon for largely centering the lives—and more importantly, the happiness—of its female characters.

Over and over, we’ve seen articles in huge publications deriding romance as formulaic, crass, and unworthy of respect as serious literature. These articles are filled with outdated references to Fabio and ripped bodices (both of which are perfectly fine) instead of focusing on the way the genre has evolved to be more inclusive—and more feminist.

While every genre has its problematic elements, gone are the days where slut-shaming, queerphobia, xenophobia, and racism are mainstays in most romance novels. By no means are all—or even most—romance novels a safe place for the identities that make up our multifaceted world and readership. I do believe the space is much safer than it used to be.

But there is still plenty of work to do.

Romance has never had a problem with popularity among readers, even when said readers wouldn’t dare admit to its consumption. I won’t pretend to have the hard numbers about this, but I know that romance is a huge money-making business.

I’ve even seen arguments that among genre fiction it is the money-making business.

And I believe we’re starting, finally, to earn some of the respect that goes hand in hand with those dollars. It’s a slow-going process, but romance is also becoming more inclusive of the full fabric of humanity. All different races, ethnicities, gender identities, sexualities, are all finding it still not easy enough, but easier to see themselves between the pages of sweeping love stories that make the happiness and companionship we all deserve seeing even more real.

And it’s not solely being left up to big, traditional publishing either.

A huge part of the diversification of the landscape has come in the form of writers who have taken hold of the reins themselves, writing and pursuing the business of publishing as independent entities.

As with most things, Black women, as much as we can, have not allowed ourselves to be excluded or erased from that narrative either.

For whatever reason (we know the reason), Black indie romance authors are not embraced in the same manner as women we’ve looked up to and considered our peers. It’s rare for us to get the same magazine spread mentions, the “bookstagram” and “booktube” features, the typical “Romancelandia” excitement about our covers featuring Black couples. Still, indie romance writers who keep their focus on representing Black love as the center of their work are still pressing forward, because we understand that notoriety is not what makes our work and our voices valuable.

It is simply our existence that does this.

Close your eyes for a moment and think about Black love.

What visual does that bring to mind for you?

Maybe it’s a little cheesy or corny, but really I want you to do it—I want you to think about Black people, together. And I’m not even talking about sexually—not to minimize the importance of that—but I mean… the romance, the intimacy, the togetherness and community of two (or maybe more) people who have been historically told that they’re unattractive, unworthy, unwanted, simply because of their race. Envision them finding themselves very much needed, very much desired, passionately yearned for, in the context of a society that still treats Black characters onscreen and on-page as if they’re only as important as their proximity to whiteness.

I don’t know about you, but that’s powerful to me.

It’s important.

It’s necessary.

For me, the visual of Black love brings to mind laughing at classic Black movies together, quoting them at random and trusting that your partner is going to instantly pick up on the reference. And if they can’t, that’s cool too, because it’s an opportunity to introduce them to another unique part of the diverse landscape of Black art.

It’s a styrofoam plate and a red plastic cup, both protected against invading insects by a paper towel, handed to you at a family reunion because you were too busy catching up to get in line to grab a plate.

It’s a hand reaching across the car to rest on and maybe even squeeze your thigh partway through a long drive, while the kids are asleep in the back seat on the way home.

It’s warmth and familiarity.

It’s resistance against a violent history that has seen families torn apart, from the horrific torture of slavery to the iniquity of mass incarceration and an unevenly wielded justice system that rips valuable pieces of family units from their homes.

It’s beautiful.

And I’m so grateful—I’m honored—to be a part of the subsection of this romance industry that keeps our eyes focused on bringing that beauty to the page.

“Black is not a genre.”

I’ll never, ever forget how hurtful it was to see that sentence on Twitter, and at the hands of a Black author who writes romance novels that feature Black characters—at least, I think so.

Obviously, I understand the sentiment of such a statement—It’s a resistance to being labeled as “other”, or having your work seen as only for a certain audience. It’s a rejection against being boxed in by a limiting statement.

The thing is, though… I don’t find the Blackness of my skin, my characters, or my work to be limiting. And truly, I’m insulted by the idea that it is.

So often, as authors—or any creator seeking to make a living from their work—we’re sold this idea of success coming from being appealing and accessible to the largest possible pool of customers. But when I look at… let’s use luxury fashion brands as the example: they aren’t appealing to everyone.

They are appealing to their customers.

The way I see it, Black romance authors who write Black characters face a non-dilemma. In a world where many—maybe most—of our neighbors can’t publicly, comfortably say a phrase as simple as Black Lives Matter with no qualifiers or clarifications, should we really consider those same people part of our target audience?

My answer?

No.

There is very little reward in trying to force others to see your humanity—even less in convincing them that your happily ever afters are heart-warming, sexy, and realistic. There are those who want to be more inclusive than they actually are, so maybe they’ll purchase to show the internet they’re a “colorblind” ally. And, absolutely, there is a portion of the “mainstream” audience who are not Black, but are truly interested in, and enjoy, Black love stories.

Is that number, taken as a whole, larger than the Black audience who is interested in your work? I’d love to see numbers supporting that, but until I do… I don’t. What I have seen are Black authors lamenting that their publisher put people of a different race—or no people at all—on their covers to “mask” the race of the characters between the pages. I’ve seen Black authors talk about their books with Black people on the covers not selling as well. I’ve seen publishers come under fire for quiet comments about how Black people don’t sell.

And all this leads me to believe that… Black romance doesn’t sell… to white people.

Black readers, though?

We adore it.

The Black women who converge on us at signings and conferences geared toward “us”, their excited comments on social media, the way they push our books up the Amazon charts every time we release a new tale of Black love—they all love Black romance, and they cannot get enough of it.

At these events—like Girl, Have You Met, which was established by me and my friend and indie romance peer Alexandra Warren—we get countless thank yous from women who’ve never been to anything like it. A room full of hundreds of Black people, celebrating relationships and love that looks like what created us, what we live, what we dream of… it’s the kind of thing that makes the late nights, early mornings, headaches and tears all worth it.

Because the celebration of Black love means something to them.

That was why Alexandra and I created Girl, Have You Read (which focuses on the books, the same way the event focuses on meeting the authors) in the first place. There was no central place that would give indie authors any respect or attention that also put the celebration of Black relationships at center stage.

So instead of whining and complaining, trying to force ourselves into a space where we clearly weren’t valued… we built it.

And they came.

And those readers show up for us, every single day.

So why in the world would they not be my target audience?

And why in the world would publishing ignore that?

Sure, maybe more “mainstream” romance has a wider appeal, but so do original Cheetos. I highly doubt the specialty flavors sell as well, but it doesn’t keep the company from making them available to the people who love them.

They even put them right next to the other Cheetos—in their own box, for easy access for people who are looking for them; no one wants to dig around through a whole bin of one type of snack, looking for that lone copy of something that’s different, but speaks more to specific taste buds.

So… maybe the publishing industry could take a few hints from the snack companies.

Back to what I referred to as a “non-dilemma” though.

Black women support Black romance—defined as a story focused on a relationship where all the people in that relationship are Black. Do Black women read other things—absolutely! We have incredibly diverse palettes.

But we deserve to see the relationships that created us—the relationships that we coveted and observed growing up—and the relationships we’re in reflected in this industry we love to consume.

In all pairings.

I believe that publishing has, slowly, been trying to make a change. But when it comes to showing us together… there’s been a disappointing lack—and simultaneous gaslighting—that has been incredibly disheartening to witness. When you can have panels full of romance authors who happen to be Black, given an incredible stage to gush about their work, their characters, their readers, that’s amazing!

But then you look at their covers and there are no Black faces.

Or, a hot new book is coming out, and there is a Black woman on the cover… but she’s the only one between those pages.

We’re supposed to see it as progress.

I love that those Black authors are making their names in publishing, and getting the accolades and applause—I would never minimize their work, or the heart and effort they put into it. They deserve to be celebrated.

But it’s not inspiring, for me.

Because what I see is, you can be Black, and win, as long as your characters aren’t Black too. Or if they are, maybe just one. As long as it’s not too Black. As long as they don’t use certain language. As long as they don’t do certain things. As long as they’re normal.

When publishing gives a Black woman who writes Black relationships the same press and promotion as it gives authors whose work focuses on majority non-Black leads—and that Black woman’s work doesn’t have to be filtered first through an “acceptable negro” sieve?

That will be progress to me.

I wonder what changed in the public consciousness that makes seeing Black people loving each other in popular media such an anomaly?

As far as I can tell, even the Black love interests in mostly white shows, movies, and books, are presented as less of a whole, fully realized person, more as character development for the white people the show is really about. Yes, there are those where this isn’t the case, but it’s unfortunately prevalent. Much more visible than modern examples of Black people loving each other.

What is the message in that?

That Black people being loved is only as valid as the white person they’re in the relationship with? But only, of course, if there isn’t too much attention given to their Blackness—but really, that’s a whole other topic.

The problem is not the existence or popularity of interracial romance. The problem is that instead of taking space from over-represented white narratives, Black romance gets pushed out. And we’re expected to accept it as representative of something it is not. I have not, am not, and will not argue against interracial relationships having their time in the sun—those relationships are just as important and valid as any other.

What I don’t accept, though, is being inundated with purple when I asked for blue.

Purple is fine.

But it is not blue.

This erasure didn’t always exist—in fact, there was a time when interracial relationships were taboo in mainstream—it was a big deal. Viewers threatened to boycott Star Trek. Tom and Helen Willis were played for laughs against George Jefferson’s snide comments. I’m not suggesting we go back to that; I’m wondering, instead, what the reasoning could be behind those relationships taking the place of the plethora of Black relationships that used to be so highly available on page and on-screen.

It was not always this way.

As of sitting down for this article, I’m struggling to think of any “popular” mainstream Black romance authors—the kind white readers could name — whose work reflects even primarily Black relationships. Every time I run across these lists, every time someone is asked to name their favorite Black contemporary, ninety-five percent of the time, the name given is of an author whose work is mainly interracial.

That’s not a knock against those authors.

It just makes me wonder if a white love interest—that the “mainstream” can “relate” to—is a requirement for publishing dollars. Yes, Black authors who write Black characters can get the book deal—but will they get the other things that make a book “successful”?

Will they get the catered signings, and panels with other authors gushing over their work? Will they get the coveted NYT Bestseller status, propelled by massive marketing budgets and creative promotions? Will advance review copies be sent not just to the big, notable places, but to the smaller Black reviewers and bloggers that are the backbone of the Black romance community? Some authors fight so hard against the idea of a “Black section”, but without it, are publishers making sure we get shelf placement at all? I walk past the romance section at every store I enter that sells books. I’ve learned that the chances of seeing Black faces on more than maybe—big maybe—one or two covers is rare.

I believe that, maybe, I’ve questioned this too long.

Thought about it way too hard, only to arrive at a simple answer of racism and laziness, with a healthy dose of, they don’t really see our humanity at all.

I’ve thought about it so hard that I’ve wondered why the hell are you thinking about this so hard? And… Why does it matter so much? And… Does it actually matter at all?

Well… yes.

To me, it does.

I grew up with the TV on in the background, welcoming me into the worlds of other—albeit fictional—people. The Evans family and their struggles to grow up in the projects, Sanford & Son, The Jeffersons—some of the earliest examples I can remember on TV. None of these shows gave me a particularly warm, fuzzy visual of Black love on screen—in fact, they were a bit horrifying in their realism—but the drama and comedy and emotion of all of them paved the way for more “modern” Black TV.

The Cosby show. A Different World. I won’t wax too poetically about the Cosby show for obvious reasons, but if I look solely to Cliff and Clair as fictional characters, they were game-changing for me as a child. This wealthy Black family who loved each other.

What a concept!

And then there was spinoff A Different World, which first introduced me to so many concepts—dorm life, sororities and fraternities, and… Black Love. I didn’t know what that was back then, probably because it wasn’t a big deal; it wasn’t uncommon to see Black people in love with each other on TV. Ron and Freddie… Ron and Kim. Whitley and Dewayne. Plus all the other interpersonal relationships that happened in between. That show very much set the stage for me to see Black Love as normal, and desirable. Not flawless, or perfect.

But beautiful.

My entire world opened from there.

Hanging With Mr. Cooper. Sister, Sister. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

Mark Curry, Holly Robinson Peete, and Dawn Lewis cycled through baddies, male and female, as the norm. Tia and Tamera kept a cute Black boyfriend—and I’ll admit that even though they always wanted their annoying neighbor Roger to go home, I wanted him to come to my house.

Will, Carlton, Ashley, and Hillary?

Always with Black love interests.

Martin. Living Single. The Wayans Brothers. The Jamie Foxx Show.

Introduced us to everybody in Black Hollywood—cameos left and right, as love interests and otherwise.

And I felt so seen.

Especially once Black TV came around to Moesha, The Parkers, then Girlfriends, One on One, Half and Half.

More recently?

The Game. Atlanta. Queen Sugar. Insecure.

These are the relationships I watched through my formative years, the experiences I internalized—good and bad—that made me feel seen on screen. Black Love was never a last resort for these shows. It was the center, it was the lifeblood—and it took nothing away from any show where that wasn’t the case. But they gave those of us who felt and appreciated that, who were looking for that—exactly what we needed.

We don’t really have that anymore.

I already know, dear reader, that your brain is coming up with a list of shows that defy my words—of course there’s not an absence of Black Love on TV—and you’re about to prove it to me. But I want you to filter out any shows that didn’t premiere within the last five years. I want you to filter out any that aren’t a predominantly Black cast. And then, only show me the ones that are available outside of premium channels/streaming.

Yeah.

Exactly.

Because even if we include the shows from prestige TV and the streaming networks… the numbers just aren’t great.

And they’re even worse for books.

Of the last ten Black authors who earned the status of New York Times Bestseller, whose book centered a romantic relationship, how many of those didn’t feature a white love-interest?

Were there any?

No.

There were not.

Again—not at all a knock against those authors, but it feels pretty homogenous, right? When you take these books that are supposed to be about Black people, and you compare those relationships to the real-life statistics about Black Love… now do you see the point?

To get romantic storytelling that gives readers the same feeling as those shows I mentioned, one would have to turn their sights to books that haven’t been filtered through the lens of an industry that doesn’t appreciate—and certainly doesn’t reward the pairing of Black characters with each other.

If I want the soul, the nuance, the respect, the love of culture, the rejection of the white gaze, the full embrace of “Black on Black” love, I have to go where all of that is given without reservation. I have to turn to authors who love Black women, who are proud to state that while anybody can read and enjoy the work, it’s for us.

I have to turn to where Black is not only absolutely a genre, but a mainstay—an imperative. Not monolithic, not always stereotypical, but absolutely all-encompassing.

Black Indie Romance.

The baddest chick in the room.

I can go to Black Indie Romance to find absolutely anything I’d like to read, centering Black characters. I… could actually turn to my own catalog for many different genres, but honestly—I would be in great company, amongst other authors who are writing for Black women.

Our mentions of grey sweats and head wraps and door-knockers and fish plates don’t have to be watered down, reworded, or explained; they are simply understood, because we’re writing, to some degree, about the lives we lead. And when we expand those horizons beyond everyday people, into the paranormal or ultra-rich or dystopian, or whatever, those little Easter-eggs—those tiny love letters to our Blackness—they still have a place.

When I’m writing, there are only rare moments of doubt over whether or not my audience will get it. Because my audience is… me. My audience is my friends, my peers, my sister, my mother, the woman I share a nod and a smile with in the grocery store because there are so few of us around town.

It’s a beautiful kind of freedom, to me.

Freedom from pressure to make my work more accessible, more mainstream, more relatable to… the masses.

To white people.

To make it less… me.

It’s my most sincere hope that one day soon, the publishing industry will see the value of some Black author who writes Black romance, and will give her all the resources she needs to access the readers who are hungry for work that makes them feel seen. I hope the industry doesn’t dull or dilute the cultural references or specificity. I hope they don’t water it down to make it palatable.

I hope they understand that they can set a new standard, instead of adapting to one built by centuries and decades of racist beliefs about how Black people connect with, relate to, and love on each other.

Just because something is the way it has always been, doesn’t make it the way it always has to be.

That could be a pipe dream. Or it could be right around the corner—the very best of luck and well wishes to you Sis, whoever you are, wherever you are, if you’re reading this. Enjoy that time in the sun, and make it everything.

But in the meantime, until that happens—and while it’s happening, because we aren’t going anywhere—I know I can find all the warmth and support in the world among my people.

The Black Indies.

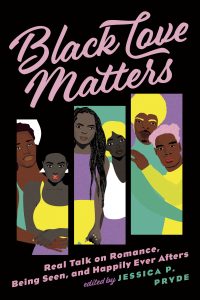

From Black Love Matters: Real Talk on Romance, Being Seen, and Happy Ever Afters, edited by Jessica P. Pryde. Used with the permission of the publisher, Berkley. Copyright © 2022 by Jessica P. Pryde.. Available from Amazon and Bookshop.